As we toured the Our Linen Stories exhibition, it became clear that there are lots of elements that make up the ecology of design. This section of the exhibition celebrates some of the ways in which we can support designers to generate interest and income for their local communities.

For example this can be done by introducing young children to a new technique for the first time, or supporting established designers who are forging a career for themselves. There are many ways that we can nurture design in the linen industry, and enhance local communities in the process.

The grand houses, castles and palaces of Europe signified their owner’s wealth with important household items including the presence of ‘suits’ of damask table linen, or ‘napery’. Preeminent in the production of these were the weaving towns of The Low Countries in Belgium and The Netherlands.

In times when Scotland’s rural agricultural economy was controlled by the land-owning aristocracy, local weavers could supplement incomes through commissions from grand houses. As weaving technologies were introduced from abroad, so skilled Scottish weavers could rival their continental competition: they were commissioned to create napery patterned with aristocratic armorial symbols often set amidst nature-inspired motifs.

Following the 1707 Act of Union with England, the linen trade was specifically geared for development in Scotland. This was reflected in the award of prizes to designers of damask and the incentivising of those able to improve local weaving skills and loom technologies.

New Drawing Schools were established in Edinburgh and Dunfermline specifically to encourage the design of linen damask. Attendees were often those from weaving families with an intimate working knowledge of looms and linen production in addition to a flare for design. It is evident that the earliest independent designers managing a Creative career in Scotland were in fact those designing linen damask.

Scotland came late but lustily to industrialization and linen manufacture was our first great national manufacturing base. As textile trades in linen, cotton and wool peaked in the nineteenth century, the value of good design was recognised through awards at ‘Arts and Industry’ events throughout the country.

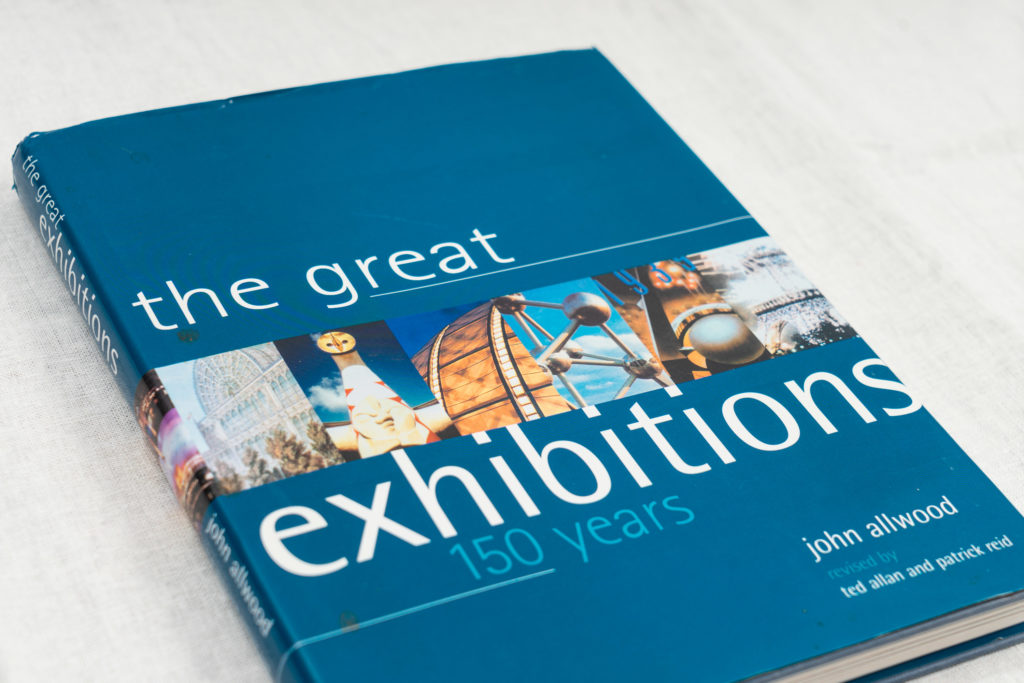

To encourage and enable potential sales abroad by exposure to foreign buyers, the great International Exhibitions beginning at Crystal Palace in London 1851, offered Design Awards across all sectors. Rivalrous Linen Manufacturing Companies from Scotland, Ireland and The Low Countries vied for coveted awards: key individuals could gain ‘celebrity designer’ status with a Medal from the Great Exhibition.

Awarding prizes for quality design has a long history and amongst our core exhibition, we show the work of several award winners. In the realms of tapestry and textile art, The Cordis Prize originated from the passionate commitment of one local Scottish patron for example and has matured into the production of an international competition, allied exhibition and seminar.

Individuals and organisations continue to nurture design talent by commissioning contemporary work. Journeys in Design is delighted to have given opportunities to Scottish design talent of several disciplines through Our Linen Stories initiative.

Monogrammed Linen

From a set of household linens bearing the family monogram and crown, kindly offered for exhibition by Lady Bute

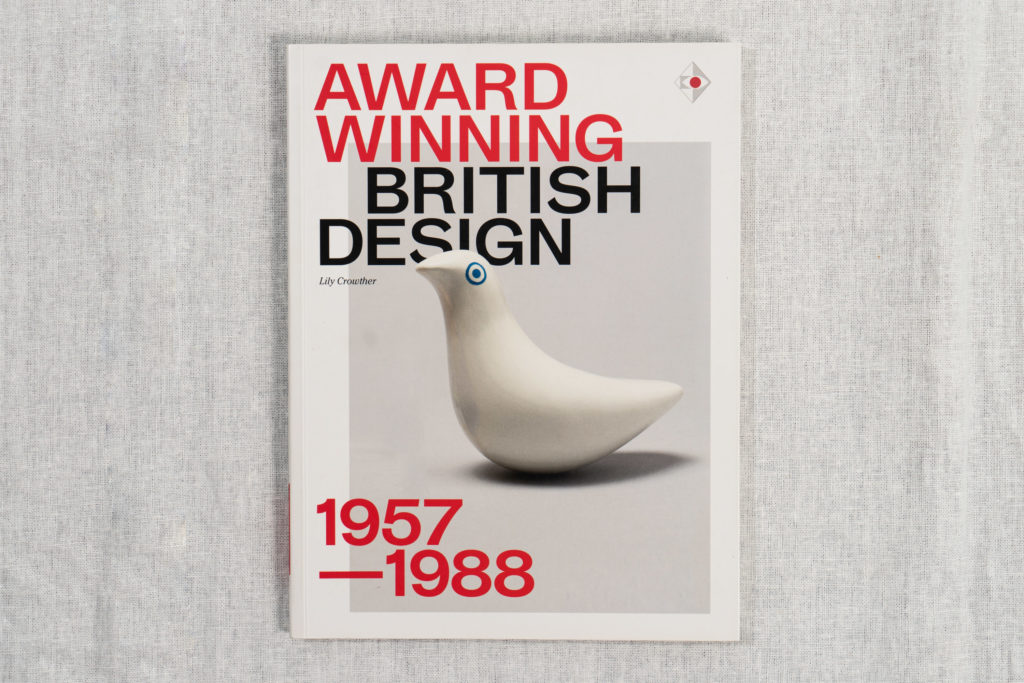

Award Winning Design

Book by Lily Crowther. ‘Award Winning British Design 1957 – 1958’ Pub. V&A Publishing

The Great Exhibitions

The Great Exhibitions book by John Allwood. Pub. Exhibition Consultants Ltd.